It’s hard to make a selection on works on Caribbean insular water systems and its relation to spatial development in general and Curaçao in particular. But these publications are definitely worth reading.

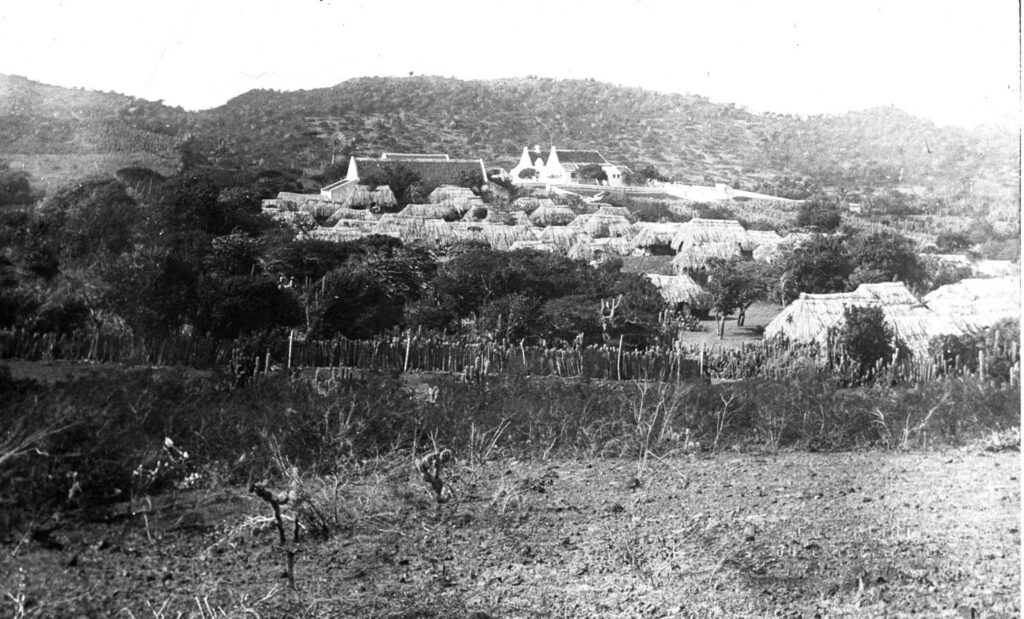

Waterplantage Heintje Kool Curaçao. Nationaal Archief Curaçao

1. Freshwater resources in the insular Caribbean : an environmental perspective

by Tamara Heartsill Scalley (2012)

This research is invaluable in understanding the water systems and water challenges of the insular Caribbean. The most important take away from this research for me is the importance of ephemeral streams. In the Caribbean they are called guts, ghuts or gullies. In the Dutch Caribbean islands they are called rooien. Fresh water bodies like lakes, ponds and streams can be absent, or at least invisible on the land surface for long periods of time. Only after sufficient rainfall ephemeral streams will appear. Tamara Heartsill Scalley argues that their importance for insular fresh water (resource) management and ecology can not be overstated. Due to their fleeting nature the ‘invisible’ stream beds are often disturbed, neglected and destroyed during urbanisation and / or land use changes. This negatively effects the water retaining capacity of the island and increases flood risk. On the Werbata Jonkheer Maps, the first topographical maps of the Dutch Caribbean islands they were recorded for the first time. The maps drawn by cartographer J.V.D. Werbata between 1911-1915 show the delicate networks of rooien on the Dutch Caribbean islands for the first time.

If you want to learn about these maps and their fascinating origin story please read: Werbata The Werbata Jonkheer Maps: The first topographic maps of the Netherlands Antilles, 1911-1915, Caert Thresoor, 24, 2005 nr. 1 by Van Der Krogt, P., (2005).

Rooi with dam after rain. Photographer Harry Verstappen

2. Works about deforestation in the Dutch Caribbean

by J.H. Westerman (1952) and R.W.M. Derix (2016)

“…man finds to his dismayed surprise that he conquered the forest too well. He finds that although too much forest was a handicap to his progress, the absence of forest is an actual menace to his agriculture, his water supply, and to his very existence.” (Gill 1931 qtd. in Westerman 1952)

With this quote Westerman illustrates in his report ‘Conservation in the Caribbean’ (Westerman, 1952) the dire state of the forest in the Dutch Caribbean, the impact of deforestation on the water cycle and fresh water resources and the lack of efforts for conservation and reforestation. The relation between land clearing and deforestation on deterioration of soil and water resources was well known in the Caribbean. One of the worlds earliest legally protected nature reserves is Main Ridge Forest on the island of Tobago, that became protected by the Crown in 1776.

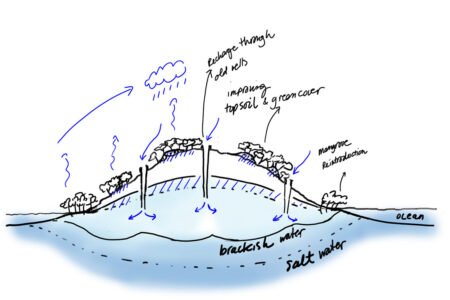

According to Derix (2016) the landscape and vegetation in the Lesser Antilles changed due to fluctuations in geological and climate conditions and the impact of human activity. With the arrival of the Spanish the exploitation and logging of wood (a.o. for valuable dye wood) on a commercial scale began while the introduction of grazing cattle prevented substantial regrowth of the green cover. The Dutch continued logging until near total clearing of dry woodland and wet mangrove forest. Increased flood risk and soil erosion, loss of water retaining capacity, decrease of recharge of groundwater resources all resulted in environmental degradation and a disturbed water cycle.

Huis en dorp behorende bij plantage Groot Santa Martha. Fotostudio Soublette et Fils_(1890-1920). Source: Het Geheugen.

3. Het Curaçaose plantagebedrijf in de negentiende eeuw (The 19th century Curaçoan plantation enterprise)

By W.E Renkema, W. E. (1981).

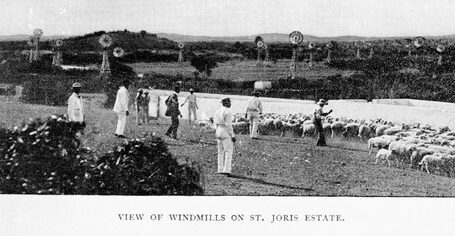

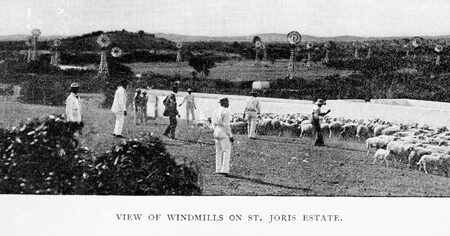

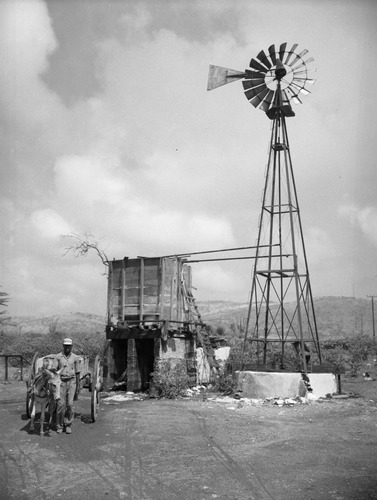

This book reveals how the Dutch tried (and failed) to establish a plantation economy in Curaçao. One of the take aways from the book for me was the fact that the islands’ struggle with fresh water shortages did not prevent the commodification of water and actually stimulated the establishment of the so called waterplantages. These commercial water plants, operated with American wind-water mills, were able to abstract large quantities of ground water. Cargo and military vessels and later cruiseships, urban population and governmental institutions were the most important customers. Overexploitation of water resources and unequal distribution contributed to extreme water shortages for poor islanders and small holder farmers and the death or inevitable culling of their livestock.

4. Olie als Water (Oil as Water)

by Jaap van Zoest (1977)

This book continues where Renkema’s book ends. The discovery of oil in Venezuela marked the beginning of the 20th century oil boom and the development of tourism in Curaçao The water intense oil industry demanded increased water supply. The Curaçaose Petroleum Industry Maatschappij (CPIM) exploited several waterplantages by taking over exsisting . The waterplantages supplied the industry itself, its’ so called ‘oliedorpen’ where the company housed their growing workforce and third parties. Even in extremely dry years CIPM would rather sell around a third of its water production to third parties like cargo ships than supply water to the drought strikken rural population. Next to the waterplantages that extracted groundwater, the oil industry enabled the construction and exploitation of one of the first desalination plants in the world in 1928. Due to high cost the CIPM preferred groundwater exploitation to the energy and capital intensive seawater desalination. With today’s intensified scrutiny on ‘Big Oil’ due to the climate crisis this book still makes for relevant reading…

Wind-watermill. Source: Nationaal Archief Curaçao

Set up as answer and question conversation this small publication on water related challenges makes for engaging reading. Henriquez explains a.o. the different purposes and effects of the old ‘small’ dam water management system, that supported small holder farming and horticulture, and the big dam system as introduced by the government and oil refineries for water exploitation. Henriquez was particularly critical of the extreme over pumping of groundwater by Shell which resulted in the decay of fruit groves and the natural green cover.

P.C. Henriquez (1909-200) was a Curaçaoan chemist who after a period of studies and work returned to Curaçao and worked a.o. as a minister for the government. He was a strong advocate and driving force for island development and innovation. Henriquez was particularly passionate about environmental protection and cultural heritage conservation.

6. Indigenous and Afr0-Caribbean water management and horticulture

by Lydia Pulsipher and Charles Goodwin (1990, 2001)

The Caribbean islands have a rich horticultural tradition that goes back to the native Caribbean population and Afro Caribbean slave gardens (Pulsipher, 1990). With little documentation and research available on the subject it is difficult to speculate on the indigenous and traditional water management systems as developed by the native Caribs and the Afro Caribbeans to support their horticultural practices and small holder farming. In their research into the horticultural practices on the small Caribbean island of Galway Pulsipher and Goodwin (2001) speculate on this pre-modern water system (page 191). Like Henriquez before them they describe a micro rainwater catchment, soil storage and irrigation system of gullies, small earthen and stone dams and contour farming.

Kunuku house with garden. Source Het Geheugen

7. The Architecture and planning of the twentieth century on Curaçao

By Ronald R. Gill (2008)

This richly illustrated book describes the urban and architectural development on Curaçao. The book is a joy to read as well as an eye opener as it highlights the development of rural Afro Caribbean dwellings like the kas di kunuku, the ethnically segregated olie-dorpen (oil villages for Shell employees) and the vernacular back yard architecture of informal working class neighbourhoods .

The author Ronald R. Gill (1941 ) is an architect born in Indonesia and involved with the establishment of the department of Architecture and Civil Engineering at the University of Curaçao. He is also an expert on historical pre-colonial urban planning in Indonesia.

Acknowledgments

The design research project Thirsty Cities – Curaçao is executed in collaboration with NAAM. The project is financially supported by the Creative Industries Fund NL.